The Ordnance Survey Name Books are records of the fieldwork done by Royal Engineers surveyors and civilian assistants as a basis for First Edition Six Inch maps and subsequent maps. Alongside the technical surveying, they collected a rich array of information about places and place-names from local informants, and this is recorded in the Name Books in tabular form. The Name Books throw important light on the way this colossal exercise was conducted, including glimpses of the social dynamics within surveying teams, and between them and their informants.

Click any of the headings below to show the answers. Click again to hide them.

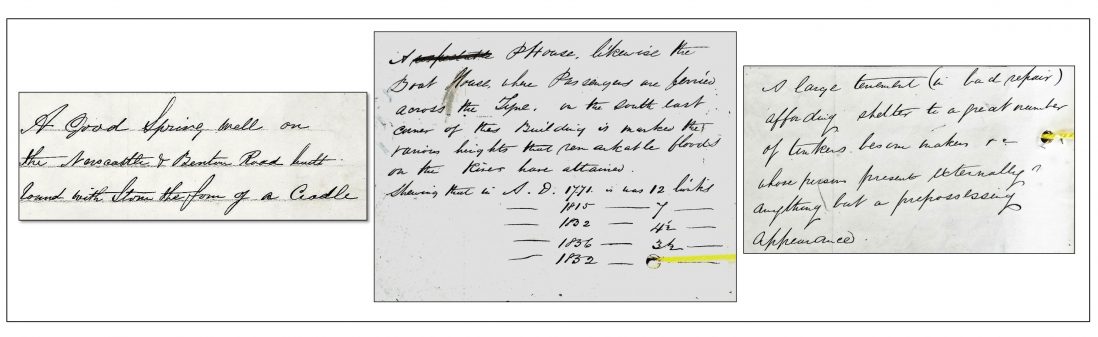

As well as throwing light on thousands of names that are all around us today (see ‘What’s their value for studying place-names?’), the Name Books help us to imagine life and landscape in the mid 19th century — a time of rapid and radical change. While some of the content is routine, many entries contain fascinating insights into landscape, antiquities, buildings, and agricultural, industrial and social history. From the Name Book for All Saints parish, Newcastle, for instance, we learn about long-gone pits, pubs and ferries, about ‘a mean looking Beer House’ called Uncle Tom’s Cabin, situated in Pity Me, and about the curious story behind Lambert’s Leap. In rural Longhorsley, we learn that Stanton Hall is ‘a large dwelling house’ that has been the manor house but ‘is now occupied by poor familys’ and ‘in very bad repair’. The Post Office is ‘A small receiving house which is also a grocers shop. Letters arrive 9.15 A. M. and are despatched 3.55. Post Master Mr Cleugh’. Chirm Wells is ‘a small stone building erected in 1836’, occupied by Mr Corrie and owned by Mr Straker, and named from nearby springs which were used for ‘drinking and bathing in a peculiar sort of water … said to be very conducive to health’ until the stream was diverted by coal mining. Nearby Chirm Pit is a small coal-pit worked by a gin and a horse.

Three Tyneside entries: the Cradle Well (parish of Newcastle St Andrew); The Ferry Boat and floods (Newburn); and Philadelphia (Tynemouth)

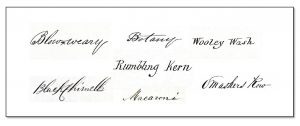

The Name Books reveal the painstaking processes — adopted nationwide — by which the surveyors ascertained the correct forms of local place-names, and selected which were to appear on the map and preserved in print for posterity. In some cases they also offer explanations. Collectively, the Northumberland books record thousands of names of settlements large and small, landscape features, antiquities, industrial sites etc., most but not all of which found their way onto the printed maps (and conversely, not quite every name on the First Edition maps is found in the Name Books). There are a few field-names but generally the survey is not at that level of detail, except in the anomalous Alnwick 336. The names that are listed and indexed combine to form a unique and invaluable gazetteer of Northumberland place-names, from the commonplace (Black Hill, West Wood, White House) to the bizarre (Shinny Gripe Lug, Bendibus Island, Hurtle Winter).

Some of the quirkier names collected by the Ordnance Survey

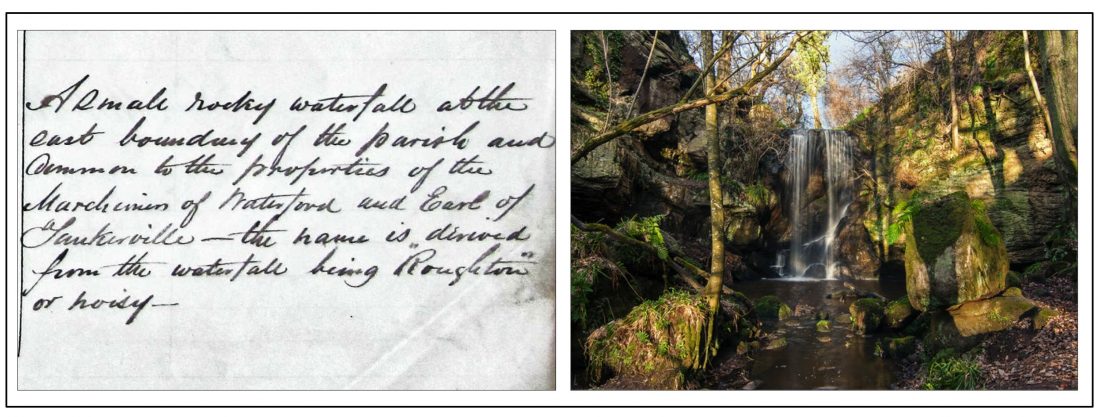

The names can be analysed in many ways, for instance according to common ‘generic’ elements such as the stream-terms burn, sike, letch, strand etc.; by language of origin (lough ‘small lake’ and tor ‘rocky peak’, ultimately from Brittonic, or fell ‘hill, hill pasture’ and holm ‘islet, dry land amidst wet’, ultimately from Scandinavian); or by type of name. There are, for instance, commemorative names such as Waterloo and Bomersund; ‘verbal place-names’ such as Seldom Seen and Glororum (‘Glower o’er ’em’); and those containing personal names, such as Lambert’s Leap or Crutchy Tommy’s Plantation. Some contain dialect words that are explained in the books, Roughton Linn among them.

Roughton Linn, as explained in the Name Book for Ford parish; now Routin Lynn, NT 9836

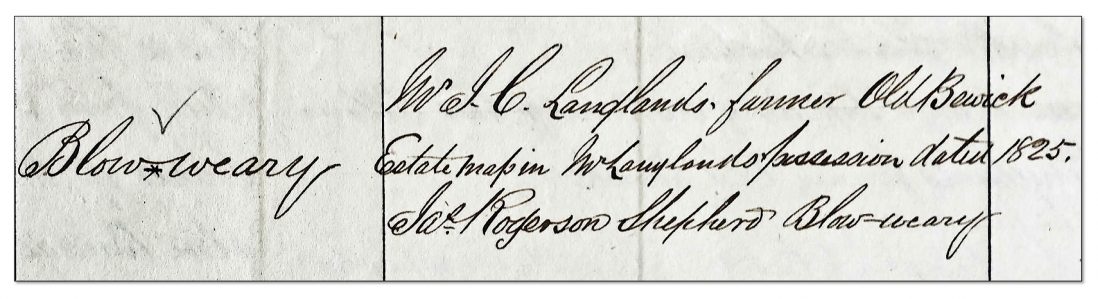

Thousands of individuals are named in the Name Books, whether as ‘Authorities’ for the spellings given; as owners or occupiers of properties; or as persons featuring in anecdotes and summary histories. Ordnance Survey policy favoured the evidence of landowners and educated men (clergymen, schoolmasters etc.), but the likes of fishermen, shepherds, foresters and publicans have also been consulted. The Name Book for Farne cites the octogenarian William Darling, lighthouse-keeper, as an authority for local names, and recalls the wreck of the SS Forfarshire in 1838 and the bravery of his daughter Grace. Women are poorly represented overall, though some property owners, pub landladies and schoolmistresses are named as authorities for local names. Some personal names evidently gave the surveyors trouble, resulting in variation in spelling. The material should be of great interest to family historians, complementing other sources.

Mr Longlands and his shepherd Mr Rogerson cited as authorities in the Eglingham Name Book

Surveying entailed recording all significant archaeological sites or ‘Antiquities’ across Northumberland and every other county. The surveyors’ expertise allowed them to make accurate ground plans, but interpretation was more of a challenge — whether distinguishing between natural and man-made features, assigning labels such as ‘Camp’ or ‘Roman remains’ or choosing an appropriate font to indicate ‘Roman, Druidical or Saxon, Norman or Subsequent’ sites. From the legend to the First Edition County Series maps of Northumberland

From the legend to the First Edition County Series maps of Northumberland

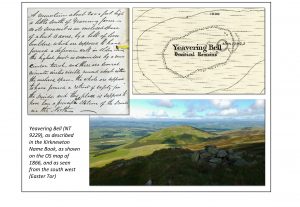

It wasn’t until 1920 that O. G. S. Crawford was appointed as the first Archaeological Officer to the OS, so the first surveyors were dependent on their own observations of sites, sometimes guided by local landowners or local antiquaries, and on earlier maps and histories, and the Name Books allow us to see something of the consultations and head-scratching. The recent maps and memoirs of the Roman Wall and the county’s Roman roads by Henry MacLauchlan, a fellow surveyor, were especially useful. Understandably, more recent archaeology has shown many of the classifications to be misguided. The more or less default term of ‘Camp’ or ‘Camp (Remains of)’ often gives way in later OS editions to ‘Settlement’ and the magnificent enclosure at Yeavering Bell (NT 9229), believed to have been used mainly in the Iron Age, is no longer considered ‘druidical’.

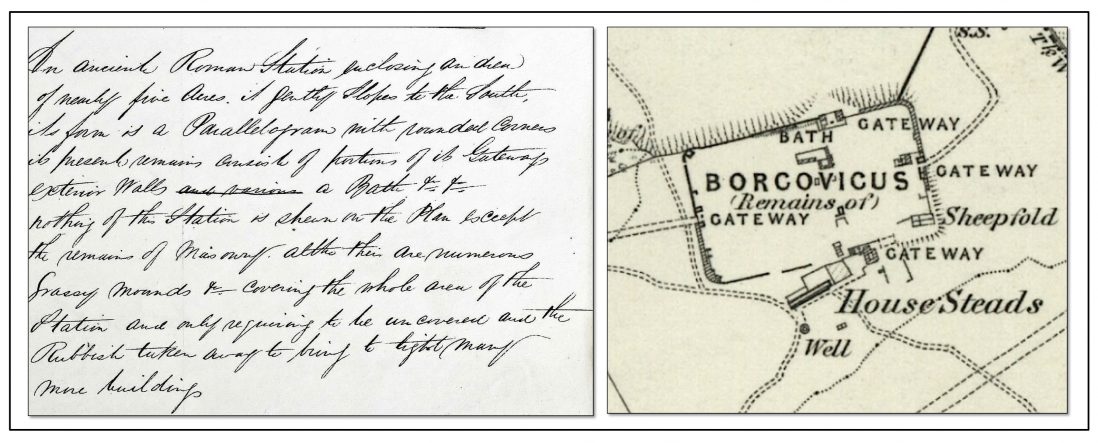

Nevertheless, there are fascinating descriptions of antiquities from all periods, including accounts of major Roman sites such as Housesteads fort before they were fully excavated, and there are (quite non-commital) reports of stones from the Roman Wall being taken away by the cartload to be re-purposed.

Borcovicus fort at Housesteads (NY 7868, now known as Vercovicium), described as still partly grass-covered in one of the two Name Books for Haltwhistle parish, and as shown on the OS map of 1866

The need for a serious national cartographic survey of Britain and Ireland was seen as especially urgent after forces had attempted to pursue surviving members of the Jacobite Rebellion through the Highlands after the battle of Culloden (1745), and the Napoleonic Wars of c.1799-1815 revived the perceived military need. Inspired especially by Major-General William Roy (1726-90), the Principal Triangulation of Great Britain was carried out 1783-1853, starting with an extraordinarily accurate base-line on Hounslow Heath, and subsequent work filled in with more detailed triangulation and measurement with chains. The acquisition of a state-of-the-art Ramsden theodolite by the Board of Ordnance in 1791 is often taken as the start of the Ordnance Survey although it was a decade or so later that ‘Ordnance Survey’ became the standard term. The first One Inch map, of Kent, appeared in 1801. The survey at Six Inches to the mile was first completed in Ireland in the 1820s to 1840s, under the indefatigable Thomas Colby (1784-52), and this pioneered the methods that were then used in the ‘County Series’ surveys of Scotland, Wales and England in the following decades.

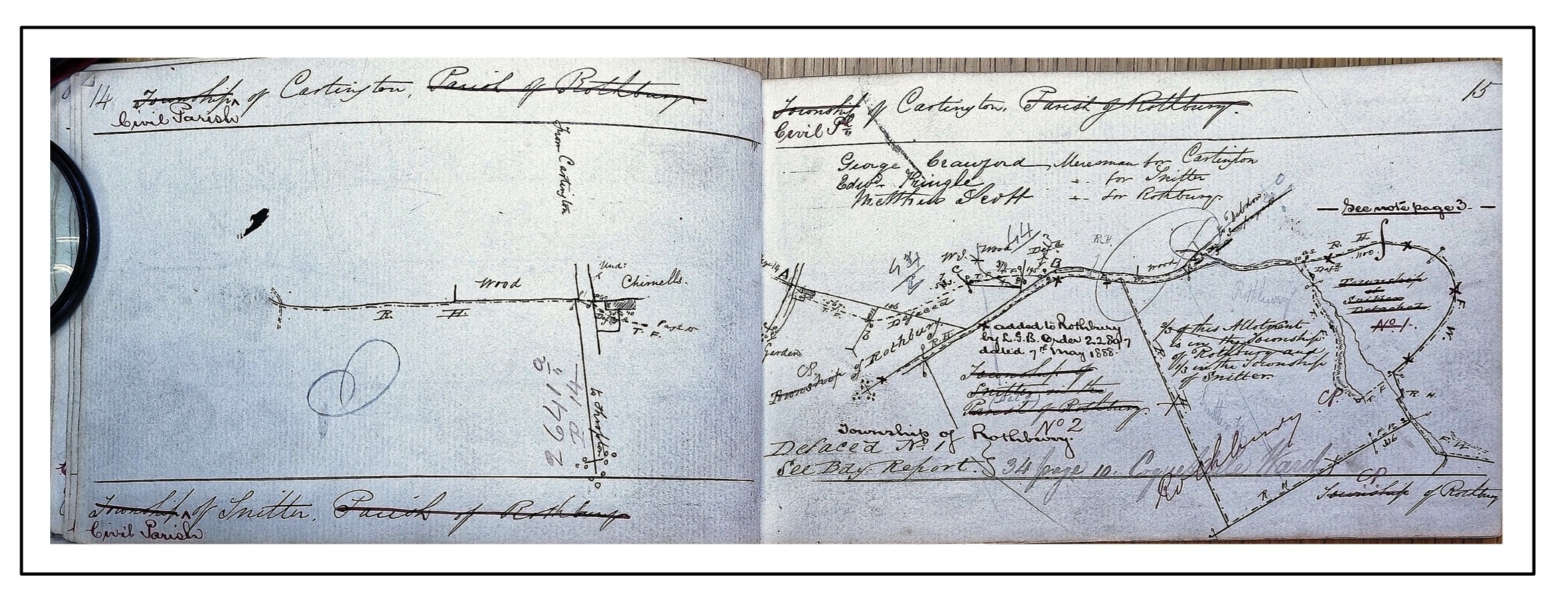

From the Boundary Remark Book for Cartington, Rothbury parish, 1858 (The National Archives, OS 26/7918)

The detailed fieldwork recorded in the Northumberland Name Books formed part of this immense project. Other documents record other aspects of the survey, including lists of parishes and townships and information about Poor Law Rates, Constables etc. in the Parish Name Books (The National Archives, OS 23) and boundary sketches and data in the Boundary Remark Books (OS 26). The beautifully engraved ‘First Edition Six Inch’ maps that embody the surveyors’ work each show an area six by four miles, and they number over a hundred for Northumberland. These maps for the entire country are among those digitised for the invaluable resource built by the National Library of Scotland at https://maps.nls.uk/

Name Books from the mid 19th century survive for most of Scotland and Ireland, but for only the four northernmost historic counties of England (Cumberland, Westmorland, Northumberland and Durham), together with part of Hampshire. The books covering the rest of England and Wales were destroyed by a bombing raid on Southampton in 1940, though later updates survive for other counties.

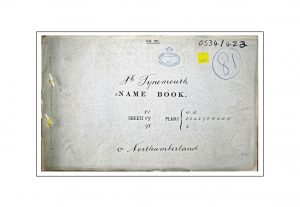

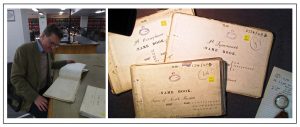

The books are typically about 38cm x 28cm (somewhat larger than an A4 page), in landscape format with thick paper covers, usually buff or manilla. Most are reasonably well preserved, though some page edges are damaged. The books are written by hand in columns on pre-printed forms and each consists of an index followed by the main book. The main book pages are normally laid out in five columns, with the information attached to each place-name stretching across the page. The columns are headed ‘List of Names as written on the Plan’; ‘Various modes of Spelling the same Name’; ‘Authority for those modes of Spelling’; ‘Situation’; and ‘Descriptive Remarks or other General Observations which may be considered of Interest’.

The books are written by hand in columns on pre-printed forms and each consists of an index followed by the main book. The main book pages are normally laid out in five columns, with the information attached to each place-name stretching across the page. The columns are headed ‘List of Names as written on the Plan’; ‘Various modes of Spelling the same Name’; ‘Authority for those modes of Spelling’; ‘Situation’; and ‘Descriptive Remarks or other General Observations which may be considered of Interest’.

The five-column layout: Benwell (Newcastle St John 34)

Alnwick 336 was produced in 1851, so belongs to a slightly earlier generation and differs in content and layout from the others. The North Shields book (OS 34/405), of 1857, partially overlaps with Tynemouth and again has a different layout.

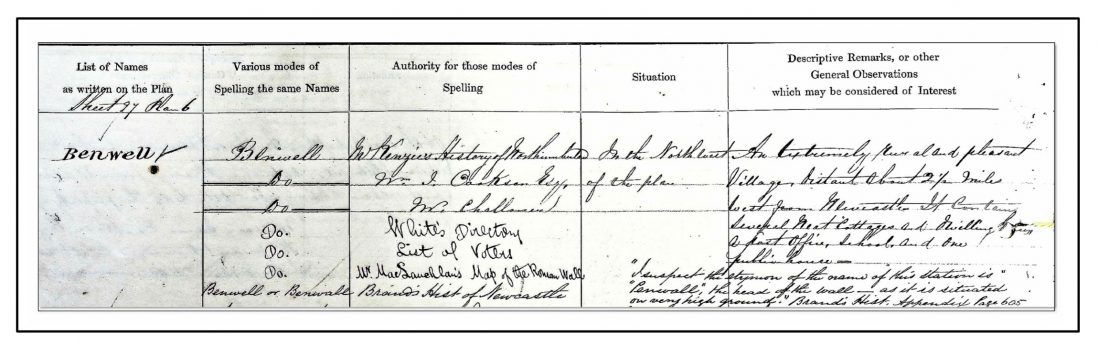

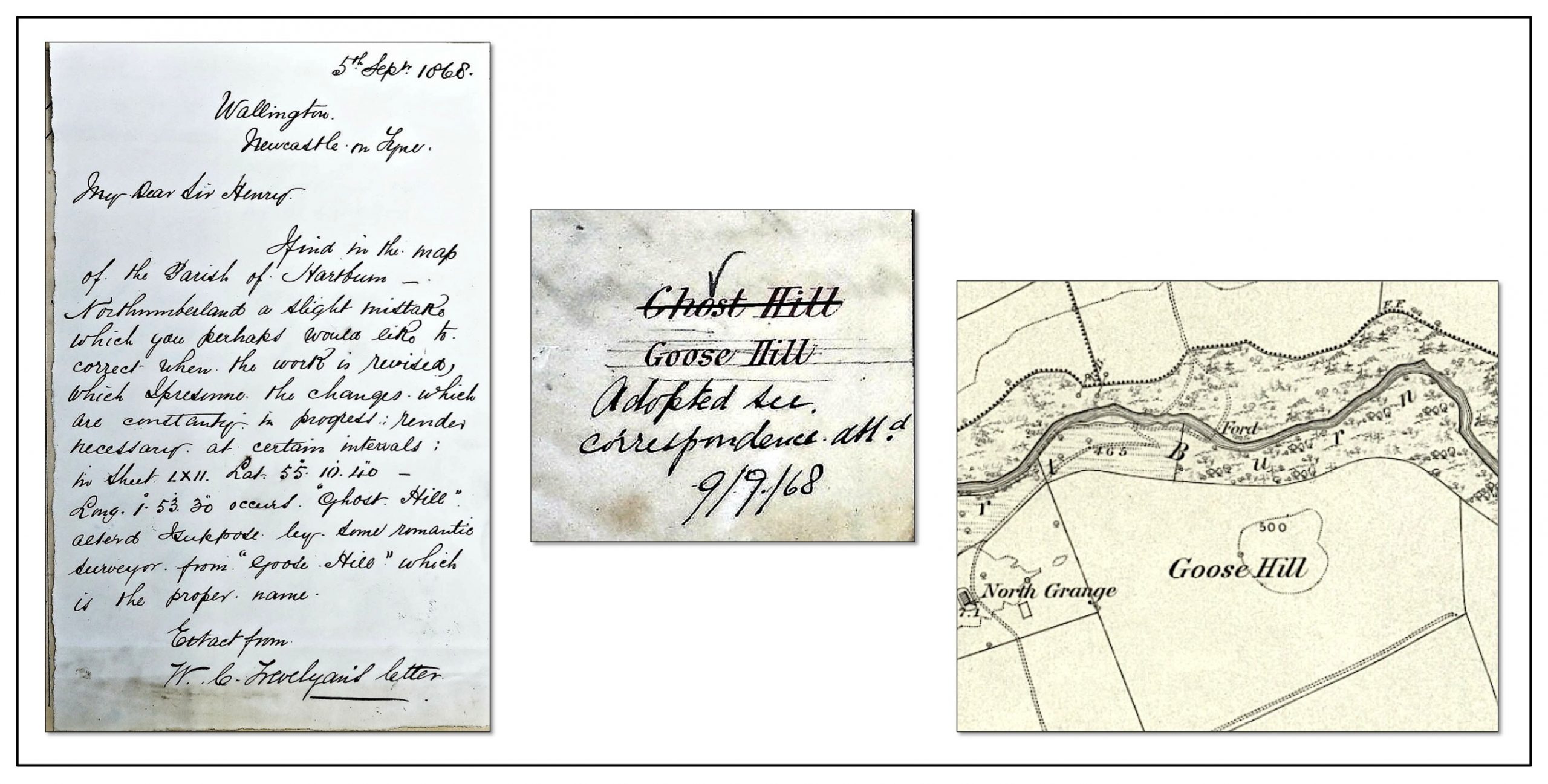

Some Name Books contain what we are calling ‘Loose papers’ — mostly letters and sketch maps from local landowners or antiquaries, offering information and opinion. These can be accessed by going to the transcription of the page where they are inserted, and clicking on the link at the bottom. The pages with loose papers are: Alnwick 334: 1, 29, 79, Alwinton 338: 31, Berwick 1, Branxton 1, Greystead 1, Hartburn 97, Holy Island 147, 231, Knarsdale 102, Lesbury 23 and Shilbottle 12.

A typical loose paper: a note from W. C. Trevelyan of Wallington Hall correcting ‘Ghost Hill’ to ‘Goose Hill’ (though the correction had already been made)

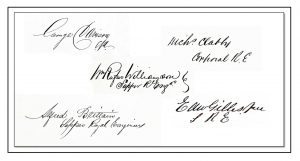

The Northumberland Name Books were produced mainly between 1858 and 1864, with a few precursors and later revisions. Part of the Ordnance Survey of the whole of Britain and Ireland, they bear witness to an extraordinary venture, with elements of research project and military operation, conducted by officers and sappers of the Royal Engineers together with a large number of professional surveyors signing as Civil Assistants. The surveyors who collect information on the ground (known in OS documents as ‘examiners’ or ‘detail examiners’) normally sign off individual pages in the Name Books, and hence we know of over forty individuals: mostly sappers, with a few lance-corporals and corporals, and with civil assistants constituting about a third (an important third) of the surveyors working in Northumberland.

Some of the surveyors’ signatures; some individuality comes through in the Name Book content, as it does in their signatures

A few of the surveyors had already worked on the Scotland survey. Several of the surnames are Irish and research by project member Byrnice Reeds has revealed some with proven Irish origins. The work of each team or ‘party’ of men was overseen by an officer, and three, Burnaby, Sitwell and O’Grady, covered most of Northumberland between them. Burnaby was a Major with Ordnance Survey experience in Scotland, but Sitwell and O’Grady were Lieutenants in their twenties (O’Grady being promoted to Captain in the course of the survey).

Army surveyors of the nineteenth century

As well as technical surveying by measuring and triangulation, the surveyors observed the places they encountered and gathered local information about places, their names and the people who lived there. They also had the challenging task of mapping and labelling antiquities and archaeological sites, at a time when the Ordnance Survey employed no archaeological experts and very little archaeological fieldwork had been done (except along the Roman Wall and Roman roads). The military and engineering background of many of the Survey personnel is perhaps reflected in their interest in viewpoints and in the quality of construction of buildings, and in their tendency to assume that archaeological sites are defensive.

The fieldwork phase was followed by office-based work, whereby information from directories, histories, earlier maps etc. could be added; and written evidence often trumped oral information. Alterations to names and other details to appear on the maps could result from this process, from orders from on high within the Ordnance Survey, or from consultation with local landowners or antiquaries.

The surviving Name Books for England are housed in The National Archives, Kew (formerly Public Record Office), with shelfmark OS 34 – with one exception: the book for Berwick upon Tweed is held, with shelfmark OS1/5/4, in the National Records of Scotland in Edinburgh, along with the Berwickshire documents.

The Name Books at home in The National Archives, Kew (shelfmark OS 34)

In more detail, the Northumberland Name Books are:

The National Archives (TNA): OS 34/331-434 (Ordnance Survey: Directorate of Field Survey: Original Name Books), catalogued at:

http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/results/r?_q=OS+34+Northumberland

(accessed September 2020)